One of the first questions you will be asked by your language service provider (LSP) when requesting a Chinese translation is if you will need “Simplified” or “Traditional” Chinese for your Chinese translation. The answer to this question is not always easy, and sometimes you may need to translate both versions.

Before we get to the answer, a little historical background would likely be helpful. Unlike the majority of today’s writing systems, written Chinese does not use an alphabet or syllabary. Chinese characters are logograms (or logographs), similar to hieroglyphs. This means that a single character is the equivalent of a single word or morpheme. In Classical Chinese, most words were monosyllabic. On the other hand, modern Chinese uses bisyllabic words much more frequently and includes numerous homophones.

This means that a single spoken syllable (e.g., shi or ma) can be represented by one of dozens (or more) of characters, depending on the meaning and tone, as Chinese is a tonal language. Mandarin Chinese contains four tones (plus a neutral tone), Cantonese includes six to nine tones, and the Shanghai dialect (or, more accurately, topolect) has five tones.

Historical linguists have traced the earliest Chinese writing system back to at least 2,000 B.C.E. when characters were engraved on oracle bones. One of the most prominent dictionaries, promulgated by the Kangxi Emperor in the 18th and 19th centuries, includes nearly 50,000 individual characters. However, most characters are rarely used, and only about 3,500 characters are needed to read a newspaper or magazine. A well-educated Chinese person typically knows about 8,000 characters. In Chinese-speaking countries, students use rote memorization to learn enough characters to become literate.

What is “Mandarin” and What Are “Simplified” Chinese Characters?

At the beginning of the 20th century, after the fall of the last Chinese dynasty, one of the most significant cultural movements – known as the May Fourth Movement – sought significant changes to traditional Chinese culture. This movement aimed to “modernize” China, and as part of that, they favored language reform.

The language reform included promoting the vernacular language in writing (as opposed to Classical Chinese) and developing a single national dialect. A single national dialect would allow people from different parts of China, who often spoke mutually unintelligible Chinese dialects, to communicate more efficiently. The result is what we now refer to as “Mandarin” Chinese.

Both the Republic of China (ROC) – now commonly known as Taiwan – and the People’s Republic of Chinese (PRC) chose Mandarin as the official, national language. However, there are hundreds of other Chinese dialects (or, more accurately, topolects), such as Cantonese, Taiwanese (Hokkien), Hakka, Shanghainese, etc. These mutually unintelligible dialects/topolects are still widely spoken in their respective regions. As a result, most Chinese speak both the official Mandarin dialect in “public” life and their “native” dialect among friends and family.

After the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) took power in China after 1949, they set about to simplify the Chinese character system. Ostensibly, the goal was to improve literacy because they believed that the traditional characters were too complex, with too many strokes, and were challenging to learn for the masses. Beginning in 1956, the government started to roll out several rounds of character simplification instructions. The “official” list of simplified characters has been adjusted numerous times over the years, with the most recent update published in 2013.

The “simplification” process for developing the new character system used several different methods of simplification. The simplification process aimed to reduce the form of complex characters and thereby reduce the total stroke count. It also created simplified characters based on popular “shorthand” versions of characters already in use in Chinese calligraphy and replacing all instances of a component (such as a “radical”) in each character where said component occurs.

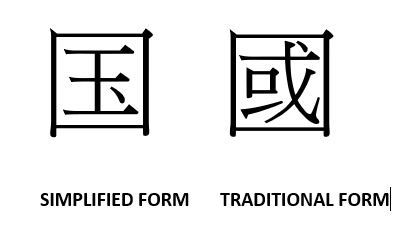

Below is an example of the simplified version (on the right) compared to the traditional form of the character Guo (country; kingdom), on the left:

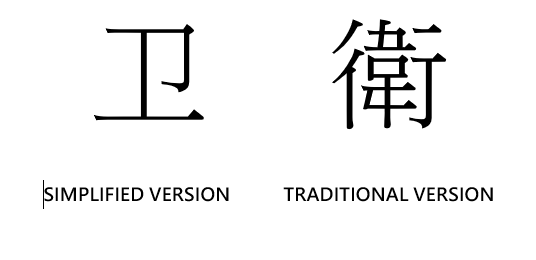

In the above example, the number of strokes has been reduced considerably, although there is still a reasonable resemblance between the two forms. Other characters, however, are completely unrecognizable from their traditional forms:

Nevertheless, while there is certainly no doubt that Chinese literacy rates improved significantly (from roughly 20% before the Communist revolution to 95% today), there are still debates about whether the simplification of characters or simply the “universal education” promulgated by the CCP after 1949. Later, other Chinese-speaking countries, such as Singapore and Malaysia, also chose to adopt Mainland China’s simplified character system.

Which One Should I Use for My Translation?

Now that we understand a little more about the history and evolution of the Chinese script, we come back to the question of do you need “Simplified” or “Traditional” Chinese for your Chinese translation.

Typically, the rule of thumb is that if your target audience is in Mainland China, Singapore, or Malaysia, you should always use “Simplified” Chinese characters. The “Simplified” character system is also the version utilized officially by the United Nations (UN).

However, if your target market is in Taiwan (Republic of China), Hong Kong, or Macau, you should use “Traditional” Chinese characters, which these areas have maintained. However, with new “reforms” in Hong Kong, they may eventually switch to the “Simplified” script to match the mainland, which has exerted stricter measures to control the former British colony, which has long had an independent and democratically-minded population.

For the users of “Traditional” Chinese characters, it is cultural and linguistic preservation. The areas that utilize “Traditional” Chinese characters have also demonstrated that the “Simplified” character system does not necessarily improve literacy, as Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau all boast high literacy rates.

While the above is relatively straightforward, one unique challenge to this question arises when you need Chinese translations targeted at Chinese-speaking individuals and/or communities overseas. In the past, when the majority of immigration to the United States originated from Hong Kong and Taiwan – both of which use the “Traditional” script – the standard Chinese script adopted in the United States for use with “overseas Chinese” was “Traditional.”

However, over the past several decades, immigration from Mainland China has increased rapidly, overtaking the number of Chinese-Americans whose families originated in Hong Kong and Taiwan. Before deciding whether to use “Traditional” or “Simplified” script in these cases, a little market research may be to determine where the majority of the target audience originated from to make the appropriate choice for your Chinese translations. In cases where the target audience is mixed, it may be necessary to provide both “Simplified” and “Traditional” Chinese versions for your document(s) to be translated.

Finally, a note of caution. Please keep in mind that you cannot translate into “Mandarin” or “Cantonese.” These both refer to spoken dialects and not the written form of the language. If you need a written translation, your only choices will be either “Simplified” or “Traditional” script, not “Mandarin” or “Cantonese.”

To find out more about our comprehensive Chinese translation, interpretation, and localization services, please feel free to contact one of our experts at (888) 341-9080 or [email protected].